How Effective Is School Menstrual Hygiene Management?

Winkler (2020) puts the discussion about menstruation in the intersection of class, caste, physiology, psychology, and sexuality into the academic collection Beauty in Blood. The range of topics which it brings into its ambit puts it down clearly that the act of making policies for menstrual hygiene management needs to consider a re-definition of menstruation – from just a normal biological process to it is fundamental for a huge section of the population (Winkler, 2020).

Here on it is to understand that policy-making for this purpose needs to consider the stakeholders at all the possible levels, within different contexts, and with different challenges. The reason for it being that individuals irrespective of their sexual or gender identity come across the discussion of what’s down there (Stubbs; Sterling, 2020). The authors discuss the context of American girls, who go through a stigmatized relationship with their bodies. They reached their primary conclusion from their literature and interviews that the anatomy below the belly goes unattended and quite often undiscussed due to inhibitions towards a personal state of the body (Stubbs; Sterling, 2020).

A primary reason for this can be the lack of knowledge among girls and boys (without making it a point of pseudo-feminism) about the variation of body and individual differences of anatomy. Thus, there seems to be an overdoing of ‘perfect’ body anatomy over ‘informed’ body anatomy.

Misinformation localized; mismanagement universalized

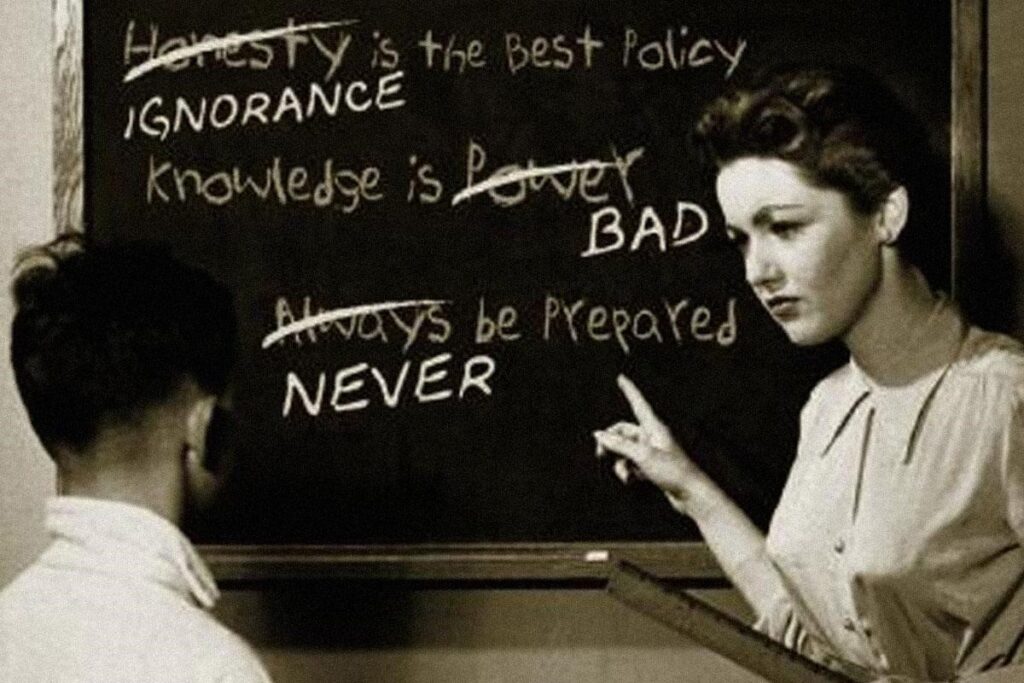

The lack of information about the naturalness of each body has led to taboos about it. It is not to demean the body always, but sometimes, out of misunderstanding the process within which it functions. Discussing the policy framework’s underlying spirit, Hales et.al. argue that the deficit of information at a young age leads to stereotypes and their re-iteration with every generation. The consequence of the wrong notions is the mismanagement of menstruation, due to lack of discussion and information dissemination (2018).

The question is if it is a localized issue or a universal topic with local variation. Multiple scholars of this area have asserted this characteristic. Discussing the Sanitation Action Summit, 2016 in the literature, Patkar (2020) emphasizes the need to frame policies for MHM in coherence with the local realities. It cannot be just at a superior level, whose effect does not reach the local context to negotiate and deal with the misinformation arising from a particular socio-cultural notion of menstruation. Further, the author draws from Bell (2019) to present the problems faced by non-binary people and the transgender community due to mismanagement and misunderstanding of menstruation.

How to encounter when not feeling responsible?

The discussion about the misinformation present at the local level leads to the investigation of its gendered nature. The kind of information present with a girl and a boy differ respectively, depending on the position they are placed in the society. There has been an underlying gender binary in this case (Erchull, 2020). The natural process of the body is taken as a determinant to divide the population for the purpose of education. It will be incorrect to assume that male students find it difficult to absorb information about the female anatomy from the very start. It emerges from training.

Erchull titles their work with it as You will know when the time is right. A list of literature reviews provided the author with evidence that boys/males were trained, and continue to be, in the perception about menstruation being a ‘woman’s topic’. An acclaimed ‘developed’ country was put under scrutiny for its sex-education training. With all the available evidence on this, the author noted that boys do not get the right and substantiate information about menstruation from the usual first source – school. Their means of knowledge acquisition are either online sources or their intimate relationship. The study covered literature from Australia, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom (Peranovic and Bentley, 2017; Chang et.al., 2012; Lovering, 1995 respectively).

Putting this problem in the local context of India, Hales, Das, and Barrington (2018) interviewed teachers from six state schools in Mumbai. From the data, it was concluded boys are not given the required information even when schemes are provided. The gender differentiation rooted in keeping the boys away from such discussions is evident from the results provided by the authors that though girls were provided pads and usage information under the Center’s Menstrual Hygiene Management Guidelines (2015), boys were kept unaware of this information and about such scheme programs in their school.

This renders the ale students ill-equipped when faced with their first encounters of bleeding either of their first family members or an intimate partner. The lack of information leads to inhibition and negative attitude among men, as was noted by both the studies in line with previous such studies. Thus, the problem at hand is not just the tabooed perception of menstruation but also a filtering structure founded upon the ‘appropriate information for each gender’ idea. This can be found in the policies that administer the MHM in India and the world at large.

Menstrual Hygiene Management or Euphemized Ignorance?

For the paucity of space and research, the information on policy addressing the misinformation about menstruation has been kept limited to India. However, some of the issues can be regarded as universal with a localized variation. The Global Baseline Report, 2018, a joint initiative by UNICEF and WHO, notes that in the survey of 2016-17 only two-thirds of the schools were found to be competent in providing facilities for women menstruating. It was post-implementation of the Central scheme of MHM Guidelines (2015).

Further, as a special note, harassment and embarrassment were emphasized to be addressed for the safety of transgender and intersex students (2018) across the countries. By a meta-analysis done on policies addressing menstrual hygiene management, Sharma and et.al (2020) examined the preparedness of the schools in India to address the fundamental needs of female students. The study notes that the magnitude of menstruating females scales up to 355 million (this minus the transgender community data). From the repository of literature collected, the authors made some important observations.

Indian schools, though came under the Central scheme of Menstrual Hygiene Management, 2015, did not have the right human resources to address the requirement. Multiple studies referred to noted that some teachers were found to be ill-equipped or insensitive to this discussion. Besides this, the lack of female teachers in some schools provided the data that school was usually not the first place of information for girls to seek information. Only 21% of girls were found in the data analysis to have been able to avail pain relievers in times of emergency. The study noted that there is an availability of pads and dust bins in some schools for girls, but the lack of separate toilets was taxing for girls. It left them with little option other than either throwing the used pads in drainage or suppress it.

Management is possible after one is made aware of the problem. But the Indian schools were found to be lacking misinformation about this fundamental aspect of biology. Male and female students were found to be below the scale of the required information to deal with the time of bleeding (Sharm et.al., 2020; Hales et.al, 2018). This problem was stated previously. In addition to this, it is to be noted that multiple studies done on Indian schooling concluded that male teachers and administrative staff were insensitive to this discussion or avoided such topics. Special correspondence of The Hindu mentioned that the education of male members of the society is important to spread awareness about the problems women go through due to mistreatment of periods (2018). S. Amuthavalli, City Engineer of Tiruchi Corporation was noted to have emphasized the menstrual education of the fathers of families to de-stigmatize the notion of bleeding.

What’s The Gap?

There is not a dearth of policies that address the needs of a menstruating female. Central policies are present, alongside international policies. They hold the problem of mismanagement of periods as a fundamental issue at the global level. From the UN’s initiative to Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, frameworks are present for schools to base their Menstrual Hygiene Management program. But the necessary step is to use the word for the problem. In the absence of direct discussion about menstruation, teachers present an unsuitable picture to the girls and boys. The presence of misinformation online can lead them to incorrect pathways, in understanding menstruation as a topic meant for one gender.

Further, the absence of perception of anatomy beyond the classic binary style leaves no space for trans-individuals to place their notes on the table for deliberations. Thus, the policy, though addresses women, does not hold womanhood in all its diversity. The gap can be bridged by re-examining the methods of information dissemination. Further, the distribution process of pads needs to stop adhering to the cis-gender notion of periods, and incorporate the idea of gender diversity. Thirdly, males of the society need to be welcomed in this discussion and need to open their minds to understand the problem of tabooing a process that is as natural as their method of periodic emissions.

Graphic design by: Itti Mahajan

Author