From taboo to talk-of-the-town: How Agents of Ishq is revolutionising sex education in India

For this piece, Tithi Karmakar interviewed Debasmita Das, the creative associate at Agents of Ishq who is a passionate advocate for sex education and using creativity to communicate important messages. With the help of their unique perspective, they develop innovative campaigns and content that challenges traditional ideas about sex and relationships.

In this interview, Debasmita shared some fascinating insights into their work at Agents of Ishq, including how they use Bollywood elements to make sex education more engaging and relatable. They also discussed the challenges of tackling such a sensitive topic in a conservative society like India, and how they and their team are breaking down barriers and making progress towards a more open and inclusive society.

To start this off, could you tell me more about your role in AOI and what kind of work you do there?

So I’m Debasmita. I work as the creative associate at AOI. I’ve been working there for the past four and a half years. I started as an intern, worked part time and then joined right after college. I handle a lot of the design team and I also work on the publishing schedule and brainstorming content. We are a small team, so everyone sticks their leg into everything. We also handle the workshops and we have that interdisciplinary approach, even in the way we work in the office feeds into our work as well.

At AOI, how do you ensure that the content you create is engaging and informative while being respectful of cultural norms and sensitivities?

So if I can describe AOI in two sentences, we are a multimedia sex ed project and we have also described ourselves as being a project about love, sex and desire. We never isolated sex from all of the different things that happen in the universe of sex and desire or the relationship surrounding sex. So I think one of the ways in which we manage to be consciously sensitive is to really take into consideration all of the different relationships and the emotions; all the drama that happens in our personal life whether it is friendship, heartbreaks we don’t create that polarisation of sex being something separate. Of course, it can be separate but for us, it is useful to look at the interconnectedness of the different kinds of relationship dynamics that influence us in our personal lives, whether it is the way we saw affection and love being shown by our parents/families while growing up. How do our different identities and patterns come into play with sexuality? So in a lot of ways, we bring in many different types of topics into the mould of sex ed because we don’t consider it to be separate. Our work in SRHR also involves law, queerness, etc. In fact, there’ve been many instances where people mistook us for being a queer organisation because we have positioned queer and feminist voices to be at the centre which happened naturally. Even history plays a big part in talking about sexuality in India, the interdisciplinary and intersectional approach towards sex is what keeps us culturally relevant because sex education can become about getting straightforward information and we think just to focus on factuality does not necessarily make information more useful.

For example, you can tell someone to wear a condom and tell them about the benefits of wearing a condom, but if you are taking into the cultural context that maybe they don’t have privacy to really be having sex in a bedroom, maybe they are being intimate in public. Are they going to have the space and how the conversation about condoms comes into place or when there are gender dynamics that also come into play with questions like, “Do you really need to wear a condom?” How do you discuss sex ed without discussing all of those dynamics, and one of the ways to make sex ed information useful is to take into consideration that cultural context. We do think we try to bring it in through many ways, like how we use popular culture, like how we think about the different scenarios that affect our sex lives and we do bring it in that cultural context by centring everything on experience. We rely heavily on the personal essays, interactions with our audience and with other people in this field who are experts to tell us what the young people working around SRHR are facing, and they tell us what are the things that matter around their sexuality in their lives. So this kind of mixed approach where we are bringing together different conversations is how we manage to keep things culturally relevant and contextual and knowing that, talking about sex ed is a lot more than just getting the facts that keep us safe.

Can you talk about how long ago AOI was formed? How has the narrative changed people’s thoughts and mentality about sex education now from when you started?

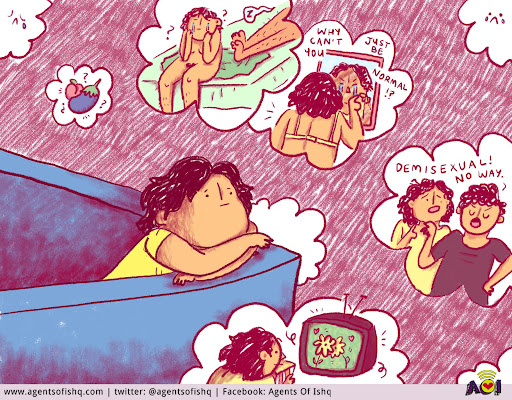

So AOI started in 2005. Paromita Vohra, our founder and creative director, is a filmmaker, she’s very famous for her films like Q2P, Unlimited Girls, etc. Her work has been very much into feminism, politics and desire. She also often says that she was waiting for the internet generation to come because it allowed you to express these ideas digitally in very creative ways. So I think the main reason why she started AOI was in reaction to the way that people were talking about sex, especially topics like consent. Sex was only talked about either in camouflage or in terms of violence and it was so rare to see sex as pleasure or a part of our daily lives and not something that is just discussed when it’s a matter of violence. Even conversations on consent would also be like, “Oh, don’t be the creep!” and there were obviously class underpinnings to the way people talked about this. So how do you have a conversation on what it means to say yes, because we always frame the topic of consent on how to say no? Questions like what to say yes to and how to say it gets ignored.

There’s also this idea that this dynamic that was always there in people’s heads is a bit of the colonial mentality, that India was the land of the Kamasutra and magically we got repressed and that the west is forward and here, we are backward. Sexually liberated means embracing a certain kind of sexual inhibition. Of course, all of the information floating around is not contextual. A lot of it does not resonate so how can we make said material that actually makes sense of all of these different dynamics which are there in our cultural context and how does it take into account the things that give us pleasure and what it means to have a good sex life to an Indian? In the end, we should be able to decide for ourselves. We don’t necessarily need someone else’s blueprint of a great sex life, especially when it’s coming from a different cultural context. So I think those are one of the many reasons why we wanted to talk about sex in India since it is the land of the Kamasutra (still the first line in so many articles!) Even if we are talking about erotic texts, there are so many other texts out there and even the Kamasutra is not perfect, it has its ups and downs and has its own limitations. So how do you have a conversation that is genuinely useful to people? was one of the reasons Paromita started AOI back in 2005 and I joined a few years later as an intern. AOI has been around for 7 years and I have been around here for 4 and a half years.

In this time, there’s obviously been a shift in the sense that initially there were few forerunners of sexuality education like Tarshi, and only few sex toys companies were present, and now over time, you do see that sexual health and wellbeing as a topic is something no longer confined to the social sector, especially SRHR space, it’s a part of a conversation very much in the public eye now. Even sex toys have become a hot topic, and you have a lot more people wanting to be Sex Ed educators online and putting out a lot of content. So there’s an openness to discussing sex and recognising that it was a conversation that needs to happen. Also we don’t see unexpected spaces where we slowly see new generations of older people are being more open, like in the past year, AOI started printing out material and going to physical spaces to sell some of our booklets, because you can have a different kind of interactions with people there which you might not find online and we saw so many parents coming and asking us, “My kid is 5, but when he turns 10, do you have any material that I can use to have the conversation with them?” We had also once done this survey called “Sex Pe Charcha” where we asked people how do you talk to your parents about sex which was done 5-6 years ago. Then we asked the same question a few years later, people whose parents they still knew would not be comfortable talking about sex but there was a huge shift in the number of parents trying to communicate in their own small funny ways, no matter if it is successful or not, have that conversation with their kids. So you will see that openness, even in the older generation. Even in terms of queerness, we will see many people approaching us on how to tackle the intergenerational gap of understanding of queerness, because they recognise now that younger people are much more confident exploring their sex lives in order to understand their sexuality. A lot of people in the older generation who haven’t had that opportunity to know about sex, sexuality and queerness, they also want to catch up with the lingo. We have been doing workshops with teachers, it’s not that they want material that they can just teach to young people but they also want to know that since young people are already so far ahead, how do we catch up to them, how do we understand their needs and how do we come to terms with this ever-changing world of sexuality, because conversation around consent is not so easy anymore because there’s an entire digital world that is a playing field of flirting, texting and sexting, so even consent is operating at a different area and having that conversation now because we now recognise that a lot of these changes are happening and much more people are involved.

Can you talk about how AOI’s approach to sex education differs from more traditional methods and why do you think this approach is important?

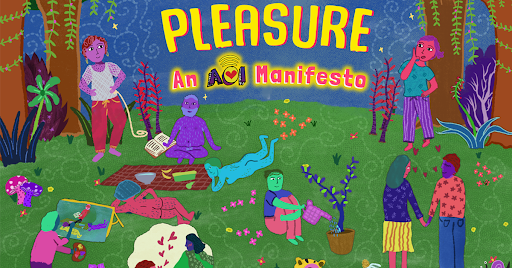

I think the primary framework of AOI’s work is pleasure politics. We believe that pleasure is about having fun and feeling comforted which in itself is not a shameful thing. It’s something that is a part of life and it can be a very open and inclusive framework. When you have a group full of people who might be having very diverse experiences around sex, how do you make it comfortable for them to enter the conversation easily without feeling like, “oh no, i don’t know this information and i won’t be able to understand this” or “Can I really be a part of this conversation?”. Pleasure as well as sex is something that can mean different things for different people and many of them are in different stages. So how do you make it comfortable for people to enter the conversation without the discourse of being polarised from making them feel unseen, that’s why we feel like pleasure has a very inclusive framework. When you watch something together that you enjoy, it gives you a starting point for a conversation that allows people to enter the conversation. For example, when you ask someone about what romance means to them, it opens up the space for them to talk about their experiences. It allows them to feel comfortable enough to be a part of that experience.

We once put out this material on this concept of mental sexual health that Dr. Amrita Narayan talked about, which stated, “because we have such a negative attitude towards pleasure, like eat your greens first, and then you can have dessert.” The inherent negative attitude towards pleasure is there in everything, not just in the matter of sex. It’s also very much tied to this idea of purity and we think it makes us lesser to watch a popular culture movie or enjoy something that is made for enjoyment exclusively, we think it’s not smart or important enough. So, we want to address that negative attitude towards pleasure because of course, if you are talking about pleasure and sex education, you have to make sure that the way that you do it is pleasurable too. A lot of our approach is to have content that makes people laugh and crack jokes that make people laugh, to make sure whatever we are putting out is not jargon-heavy, it is not loaded with any kind of moral policing or judgement, so people can really come and express what kind of pleasure they are into. For example when fans write thirsty tweets for their favourite celebrities, people can dismiss us for being extremely frank with our content but it is a part of our approach because if we are not comfortable ourselves being flexible with our audience, then how can we be talking about pleasure? We know pleasure is important in part of trusting and knowing yourself and being able to fight against all of those oppressive structures that try to limit your pleasure.

Gender tells you that you don’t deserve that much time for leisure and that you are bound to your responsibilities. Heteronormativity tells you that in relationships, there are certain ways that are legit rather than multiple affairs which might be very meaningful to you. There are so many ways in which you are told to not take pleasure seriously, and pleasure politics is about trusting our senses. It’s about making sense of the world through that. So that we are able to sidestep these rules that have been made for ourselves and allow other people to have those pleasures, for example, just because you are a disabled person doesn’t mean you should not have a life or enjoy yourself. Pleasure also allows you to bring out all of the things that might be limiting your life and allows you to build a different life. For example, when talking about consent and consensual/non-consensual acts, what does it mean for sex to be pleasurable? What does it mean for flirting to be consensual? To be able to imagine those things is what pleasure politics and AOI’s approach is. We make it Desi and use this frame of pleasure to create something that people can hold onto for longer so that we are not just pointing out and understanding the negatives but to know what it is we need to build up next, even if it’s ourselves to be stronger.

How do you see the role of Agents of Ishq in promoting a more open and positive attitude towards sex and relationships in India?

I think this frame of pleasure is something that we would like other initiatives to take seriously because it is very useful in this work, often we have NGOs coming to us wanting to have a conversation on consent because we are so used to talking about consent and gender violence in certain ways that AOI then becomes the person who’s able to break out of those frameworks and have that conversation. I think this is an approach that different places can use in their work to have a meaningful impact.

I don’t think AOI’s approach in itself is something that can be useful in different types of spheres, and the fact that we centre experience and we learn and talk about things from the frame of experience and not concepts. Usually, it’s like, “here’s a concept, and here are your experiences and we talk about it through the concept.” But we enter things from experiences because it opens up the field for different things, be it acceptance or contradiction and it allows you to learn a lot more. We are open to learning about what other people’s experiences really are, then we focus on the concepts and our own experiences but we prioritise experiences overall. We have over 200+ personal stories of people’s sex and family lives, and I think that kind of a repository helps people, since there’s a lot of people who have been reading AOI, and it’s similar to growing up reading other people’s stories about their sex lives, and it’s bound to make you comfortable about yourself when you realise that the spectrum of experiences can no longer make you look around and ask yourself, “why am i not normal?” It’s when you realise that normalcy and illusion, everyone is having their own personal conundrum happening in their lives and people have so many different desires. It really requires exposure to the different kinds of pleasure that people see, the many ways that people conduct their relationships and the different perspectives as well. For example, what is a doctor’s perspective on sexuality? What about a sex educator’s perspective? What are the perspectives of disabled people and the queer community’s perspective on sexuality? The answer to all of these comes from experiences, it builds an archive of knowledge and we do feel like it allows there to be much open and easy going conversation because people are coming into the conversation knowing that there’s a place for them where they are not pressured to think in a correct way or feel like if there’s not enough things done correctly, there are not liberated enough.

We think this approach of people being experts of their own lives allows your framework to be something that can be applied in different places, so you are not deciding what is right or wrong because we would never be able to cover all the perspectives in the world but when your framework itself allows for different perspectives to come in for communities to generate their own understanding of what consent, trust or romance means. So we definitely feel like a lot of people in this field can learn from AOI’s approach.

Can you talk about how AOI incorporates Bollywood elements into its sex education content and how effective this approach has proven itself to be?

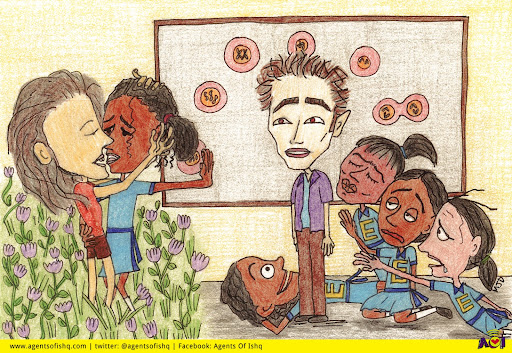

I think AOI’s approach, especially in using Bollywood, was very “us” right from the beginning because we wanted to make things relatable at a very basic level. We wanted to make it relatable and what is more predominant than the film industry around you? There’s one thing that Paromita says that is the one place where every culture has its own way of thinking about pleasure and different flavours in various popular cuisines since pleasure means different things in different cultures and what is the one place that is always engaging with these different definitions of pleasures? It’s popular culture! What does romance mean? How does one go through heartbreak? What does it mean? What drama is taking place in someone’s life? Lot of it is being represented and shown in Bollywood and like every other medium, it also reflects a lot of the bad things as well. There’s also so much of ourselves that we find valuable as well. Our approach has also been to not just see Bollywood as something we only critique but also from a different lens in order to make it relatable so people can attach their experiences. Bollywood is useless when we need a medium to speak on a topic in order for it to reach the masses quicker. It’s also such a big repository of visuals in a way that memes like kinds of expressions such as Kiron Kher memes from the movie “Dostana”. We can be sure that there’s a scandalised mom in each of us when we encounter something new. The repository of these expressions on these moments and dynamics is already present in popular culture which we can definitely use to have these conversations and a lot of people’s personal lives are influenced by interacting with the popular culture. For example, one of our interns, Ankita, had written an essay about how Emraan Hashmi’s movies led to her and her friends discovering what sex was because they were so curious about what it is that Emraan Hashmi is actually doing? If they went and asked their parents what is a condom, they would be shunned away, so they orchestrated an entire thing where one of them would get a phone with data, then they went ahead and watched porn and realised from there that sex can be pleasurable and understood what he was doing in his movies. So basically Emraan Hashmi’s movies were a gateway to see what is out there that people seem to enjoy that they find out. Then we asked people about their first moment when they remember feeling horny, and so many people said that this movie with John and Bipasha rolling in the sand on the beach in “Jism” was it. All of these moments show people’s sexualities, like some people realise they were queer because of the hots that they had for Kristen Stewart or their dislike for Edward Cullen as stated in this article. Our sexuality is evolving in conversation with popular culture. So how can we leave popular culture out of it?

For example, one thing that we have realised in recent times is that many queer people have written about their realisation about their romantic nature and their sexuality because of Shahrukh Khan. It’s such a wonderful thing because through Bollywood, people have understood things about themselves. So those are the popular cultures we can use to critique it as well. For example, in one of our videos, we made the conversation about abortion stigma much more relevant by using clips from Bollywood movies which are about “Kiska Baccha hai ye?” “Kiska paap hai tumhare khokh mein?”, etc like that. All of these things that you hear and see in the movies which you can use in a way to not stigmatise people’s consumption of popular culture but also to show a mirror to society and be able to comment on what is there. There are many ways in which we can make use of popular culture to talk about what it is that you like or dislike about it, the important thing is to develop that muscle to be able to think deeply about what we see. There’s so many people in movies, films and music, they notice so much about society and the way the concept of sexuality and love in India has changed is an interesting thing. Paromita had just done a playlist on nighties in Hindi film songs and there is so much interesting information around this part of our lives that is there in popular culture. So we want to try our best to have that be there in the conversation, otherwise, it would be boring. There is a lot to learn from Bollywood in how they make things engaging and get on people’s emotions. There is generally so much that the social sector can learn from the arts itself. So that is the role of an artist, they know how to approach things from experience and emotion and bring in concepts through that in order to change people.

How does AOI approach topics like consent and healthy relationships, especially in the context of Bollywood elements, and what kind of impact do you hope to have on your audience in these areas?

I think in terms of consent and relationships in particular, the biggest help for us in that department has been people’s personal stories. It is true that a lot of the details we come across through stories have been about the dynamics being uncovered and how they play out in relationships. So many people have written to us and if anyone wants to know about any topic, they can just go over to the personal stories section on the AOI website where you can see all the things people have written about things that happened in their relationships, as well as the emotions and the complications behind it. For example, we have an article about the idea of accountability in relationships and how the onus of accountability falls more on women than on men and how do you ensure freedom for your partner and how do you also take gender into consideration in that kind of a situation. There is a very old personal essay available to us that mentioned for the last 25 years, their husband refused them sex, and it focuses on questions like what are the dynamics of sex, even within marriage and within relationships, which even after they are important (it’s considered as the tick mark of the society), we still don’t know what’s happening in it.

But how is that dynamic playing out between people? If you don’t know that, then how do we have a proper conversation about it? If we don’t know when you are in the throes of very consensual things which turns out to be a difficult situation, knowing the concept might not always help you. So how do you help people develop the resilience to think about themselves and know what makes them comfortable and also be aware of the kind of power dynamics that are there? Knowing about these things in forms of experiences really hit, for example, there’s this great essay written by Anika and it is an account of a young woman who was in a relationship with an older man and initially she liked the attention, like oh this older person has chosen me but after a while, the question regarding how does someone start isolating you arises. How does the general idea of always listening to your elders translate into younger people not being given agency to feel like they can do what is right for themselves rather than having to rely on someone else and the idea that it’s better for the guy to be older in a relationship? So these dynamics, how do they snowball into this situation, and one can have a sensitive approach to this thing only when you need people’s stories. Because if you don’t read people’s stories, it is so easy to tell people “why did you not leave?” When you know all of these nitty gritty, you are also able to validate some of these experiences yourself. For example, someone sent us this essay about vaginismus at a time when the word was even new to us. So much of that experience is being told that if you are not having penetrative sex, it’s not really sex. If you do everything else in the world and at the end of the relationship, you are told, “we actually never had sex”. The pain and the trauma of that is something that really resonated with a lot of people, and now we can see after a few years of that conversation being brought up by that one person’s account of their story, exploration and understanding. It is something that is there amongst an audience with the knowledge that sex is so much more than just penetration which opens up the field for other things. It allows you to manage those kinds of dynamics coming in relationships. Getting into the granularity, the other experiences of people when it comes to consent is definitely helpful rather than giving them a checklist about what is done and not done. When you approach this more experientially, rather than just as a concept of consent, then you are capable of having a deeper conversation on how consent plays out.

In the past few years, consent in digital spaces, especially sexting in dating spaces, is interestingly coming up as people feel the need for it. It’s a new playing field where people don’t clearly know the rules, so there’s violations but also the scope for exploration as well. You have to keep up with people’s experiences to be able to understand what it is. One of the ways AOI talks about sex is by giving just the basics, like what is good manners when it comes to sex and flirting because understanding how to be consensual also means knowing what to do and how to flirt without creeping someone out which is always there at the back of the mind. How do you keep in mind someone’s comfort, especially when people are entering a generation where we are more sexually liberated like going out and having hookups, but we don’t always know the rules, questions like whether “am I allowed to stay in someone’s house? Do I ask or not ask? Should I only bring a condom or wait for them to get a condom?” Comes to mind. This is important to address because these are the small moments that ultimately make people feel bad and they are equally serious. Making it a happier, sensual and flirtatious world is definitely AOI’s aim when it comes to relationships and consent.

How do you incorporate feedback from your audience into your sex education content, and how has this feedback shaped the direction of your work?

Initially when AOI started, it had only created sex ed content for different NGOs, organisations and spaces working on sex ed. A lot of the materials are still being used by these places like the video “Mein Aur Meri Body” which was made in collaboration with SNEHA which is still very much in use. As a part of the project, a few stories and personal essays were put out but no one expected that there would be such a landslide response to this because it became such an integral part of AOI, even though it had not initially intended to be that way. For us, understanding the particular nuances and details of what is the information that people really need comes through from a lot of the essays and the conversations that we engage in. Once you create that space, people also find it comfortable to provide feedback. We recently did a post on different types of lubes, and people commonly asked for things they can find in their houses which you can use as lube such as coconut oil, aloe vera gel, etc. It’s understandable since it can be out of budget, condoms are already expensive for so many people and maybe the safest way out would be to tell people to use scientifically made lube instead but you don’t owe people to give them information according to the context. So you can say something like, “these are the pros and the cons, these are the things to keep in mind and then you can make a decision.” These are some of the ways we incorporate people’s feedback.

We also have “small doubts” which was a sex ed comic which started because we used to get a lot of questions which revolved around this idea of sexual etiquette, like, “how do i ask someone for a hookup without creeping them out? If I like older women, is that okay?” Questions like these were coming which made us realise that we can give direct answers to things but we can give answers which can be useful to other people as well, so generally for a larger conversation on what are the situations around consent and sexual etiquette that come up. So we turned those queries that were coming in into the “sexual etiquette” column which became a space to have these conversations. I think a lot of the ways we remain responsive to feedback is also by co-creating material. We have almost done 80,000 collaborations in the past few years, for example, the podcast with people like SNEHA, Humsafar Support Centre, Khabar Lahariya, etc. Every time we go on for a workshop, we also create material with them. “Mein Aur Meri Body” was created with young people working in SNEHA. We also did a lot of material around sexuality and disability in collaboration with Point of View. We also did a video on masturbation, especially for people with disabilities as well. We also crowd source a lot of things, many of our posts are responses people have given to us in the comment sections that we ask because even through comments, you generate a lot of knowledge from the community. When you ask, it stops us from telling you things like “yeah, this is how you flirt!”When you open the question to everybody else, you tend to get a wide perspective field of answers. We did masturbation tips for an entire month, and by the end of the month, we asked people to give us masturbation tips and it ended up being like the repository of a lot of tips people had given and it was like co-creating information and knowledge that was relevant. So one of the ways we manage to not be limited by only our knowledge of things is by collaborating with people who have that expertise and that is how we incorporate feedback in our content.

To conclude, what do you think, as people in an organisation working towards sex education, are some of the topics that you think still need more awareness?

I think pleasure as an approach which is important is something that definitely needs spotlight because it is an approach many different places can use and often we feel very hesitant to step away from the framework of “this is what is oppressing us” and stepping into “this is what gives me pleasure and allows me to think of my personal life for myself and make decisions that are relevant to my context” but taking pleasure into account, being playful as well as taking it as something that is serious is important. Taking people’s pleasures is something that is an important part of their lives and it can be a good framework to think about things. It is definitely something that you need to be able to explain a lot for people to understand. But slowly, people are beginning to realise the value of it in their lives, and there are so many projects like women and pleasure where people have instinctively understood what is the importance of pleasure and leisure and what that framework is bringing in. So we are happy to see that there’s a growing conversation around it. Even in our “love, sex and data” conference, we were able to bring together different voices who have been approaching things with that lens in their own different parts of work which included data scientists, teachers, sex educators, lawyers, etc. So I think that is definitely a conversation that has a lot of potential to go forward. It always freaks people out, especially in popular culture, because they are so used to us being terrified of being taught the wrong things, we are so afraid to admit to liking and watching Shahrukh khan’s movies or watching something that gives you pleasure since the idea of “guilty pleasure” is so prevalent.

There’s also not a lot of conversation around making sex ed inclusive and relevant for trans and disabled people. For example, there’s someone called Mira Bellwether in America where they made a zine called “fucking trans people” which was very directly about how you can, as a transwoman, have sex or how to have sex with a transwoman. She made it very much from a perspective but it was so direct and so full of information which is not available out there. Since it’s an issue of minority people not getting enough information and experiences portrayed out there, it’s not just a matter of addressing the lingo to make it broad enough but to also understand when you are making your resources, how much of it is actually addressing people’s needs? For example, in places like Transgender India, they make amazing content which people can really use, which is relevant because a lot of marginalised identities make their own materials that are useful to them because the other materials might not be taking into account their contexts and situations. So that is also something that is very much not spoken about. People, especially older ones, are also curious about what has been the history of sex ed in India and since marriage is such a goal in our society, what does sex look like in these normative relationships? What is life outside of marriage? We also talk a lot of same sex marriage equality and how older queer people are living lives outside of those boxes.

There’s also a lot of curiosity about polyamory and kink, but still not a lot of information is available even though that has been changing. In our audience, we have seen that there is as much curiosity as there is stigma. People do get aggravated by saying that polyamory is promoting cheating, so it is tricky since people haven’t really opened up to the idea yet. So, it would probably take a lot of personal experiences and a lot more voices to speak about their experiences for us to be able to break through that first level of “oh my god, how can it be handled?” So the stigma that is there against polyamory, there is curiosity and resistance simultaneously. We also did an orgasm anxiety survey which is a topic that is slowly coming to the surface, like not everyone is constantly looking for orgasms in their lives. There has been a lot of shame about it about not being able to orgasm and not having the time, space and privacy for it and feeling like you don’t fit into the idea of a sexually liberated person and we are glad to see people starting to talk about this more. Difficult conversations that can be about autonomy are also a dire need of the time, these can match up to being the epitome of sexual revolution.

You can continue to follow Agents of Ishq’s journey on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Author