Exploring Sexuality and Love through Rituparno Ghosh’s Queer Films

Queer representation through media has become one of the most powerful tools to reconstruct the social imaginary (Dasgupta 2017, 27) and to bring in conversations about non-normative identities. While cis-gendered, heterosexual representation has been omnipresent and in fact overrepresented, queer representation has continuously been invisiblized and erased from dominant discourses surrounding love, sex and relationships in cinemas. Rituparno Ghosh’s three queer movies: Arekti Premer Golpo (2010) directed by Kaushik Ganguly, Memories in March (2010) directed by Sanjay Nag and Chitrangada: The Crowning Wish (2012) directed by Rituparno Ghosh, is a step towards a more inclusive representation, specially in bengali cinema. The protagonist of all three movies is queer and is also played by Rituparno Ghosh who themself identified as a queer genderfluid person. Representation of queer characters by people who identify as queer is important to shape narratives as well as to accurately describe what an individual experiences through their perspective instead of stereotyping them into faulty prejudices. While most of the queer characters represented in movies are used either for humor or as a subplot, these three movies explore critical issues of identity, acceptability and love among non-normative gender and sexual identities.

Rituparno Ghosh’s movies brought queerness to the middle-class dining tables of Kolkata (Dasgupta 2017,28). Ghosh, who was a celebrated actor, director and writer, directed numerous movies throughout their lifetime which gave voice and autonomy to the women protagonists as well as brought into the discussion, subjects which were hardly addressed in urban middle-class households. While Rituparno Ghosh’s movies brought in queer film aesthetics and conversations which don’t usually find a place in mainstream movies, they have also been criticized for having served only upper class and caste audience, what Kaustav Bakshi terms as the ‘neo-bhadralok’ class.

Negotiations with Gender and Sexuality in Ghosh’s queer films

Gender and sexuality are the major themes around which the life of the protagonist revolves in all three movies. The marginalization that the gender nonconforming identities have to face echoes throughout the films, but there is also an assertion of the legitimacy of the ‘other’ gender beyond the male/female binary (Acharjee 2020). Along with assertion, there is also a constant battle of negotiating one’s gender and sexuality with themselves and with their family and/or loved ones. In all three movies, gender is seen as a choice, i.e, a relative amount of autonomy is given to the protagonist when it comes to expressing their gender identities. For example, in Chitrangada, Rudra, played by Rituparno Ghosh, dresses in ways which are not conventionally linked to the sex assigned at his birth. Similarly, in Arekti Premer Golpo and Memories in March, Abhiroop and Ornob respectively, dress as gender fluid or what is regarded as “feminine” and wear loud makeup, deviating from “how” they should act in accordance to their gender. Therefore, these movies mark gender deviance and show gender as a “performance”. However, this autonomy to “choose” one’s gender leads to marginalization in numerous ways. For example, Abhiroop, in Arekti Premer Golpo, is not allowed to enter the area where the shoot is being done as they are “dressed differently”. When asked to “come in plain clothes”, Abhiroop argues by saying, “What? Am I wearing a uniform or what?

In all three movies, there are undertones and sometimes also explicit remarks and confusion regarding the gender of the protagonist. In Arekti Premer Golpo, when a member of the crew addresses Abhiroop as “madam”, Momo, another crew member, played by Raima Sen, says “please stop calling Abhi-da madam, call him just Abhi.” Towards the end of the movie, Rani, Basudev’s wife, arrives on the set with the news that she is pregnant. There, she gets to know about Abhiroop and Basudev and confronts Abhrioop to let go of Basu. Abhiroop here questions her, “If I were a woman, would you have reacted in the same way?” These instances from the movie highlight how those who have non-normative identities are tried to be boxed into categories of either man or woman and how they constantly negotiate with it. Such constant negotiations were also seen in Chitrangada where Partho is hesitant about Rudra going through the reassignment surgery. Rudra here questions Partho, “Will you love me less if I become a woman?” When Rudra is mid-way through the surgery and meets Partho, the latter doesn’t support Rudra’s decision and draws a line between “biological” woman and Rudra:

Rudra: Whom did I do the changes for?

Partho: The man I loved is not this. If I have to have a woman, I would rather have a real woman, not the synthetic one.

Unfulfilled, Unrequited Love and Grief

Another common theme that runs across all three movies is how, love, and more particularly, queer love is portrayed as unfulfilled and unrequited and how one deals with the grief of losing their lover. In both Arekti Premer Golpo and Chitrangada, Abhiroop and Rudra are painted as the “third” person in the relationship. In Arekti Premer Golpo, Basu is married and Rudra is his “extra-marital” affair. The latter is aware of Basu’s marriage and once comments, “Basu, you try to maintain the status quo but somebody is paying the price for it.” Even in Chapal’s story, he is treated as an “outsider” to the relationship, who is later brought into the family to take care of his lover’s sick wife. While Chapal gave into that life and chose victimhood and exploitation, Abhiroop on the other hand, moves away when he finds out that Rani, Basu’s wife, is pregnant. Therefore, while there is a common narrative of unfulfilled love, both of them are positioned differently (Datta 2016, 176). Abhiroop’s love for Basu is however acknowledged by Rani when she says, “I also want someone to love me as much as you love him.”

In Chitranganda, from the very beginning, Partho is unhappy with Rudra’s decision to go through the sex reassignment surgery. While Rudra takes this decision to build a family with Partho, Partho insists Rudra to “be the way he is.” While Rudra goes through the surgery, Partho starts dating Kasturi, another member of the production both Rudra and Partho are a part of. This brings shock and surprises Rudra, who then asks, “whom did I do the changes for?” Rudra also tries to convince Partho by saying, “you love me, you are fond of me.” This portrays the vulnerability as well as the isolation which shapes Rudra’s life. In these two movies, unfulfilled love uncovers in terms of the hesitance of the “masculine” men to commit to “socially deviant” and “unacceptable relationships”, while maintaining a heterosexual, acceptable relationship in their lives. For their lovers, the “feminized” partners (Datta 2016), it is however different. For them, it is the pain to live with vulnerability and loneliness in order to love somebody in this heteronormative world.

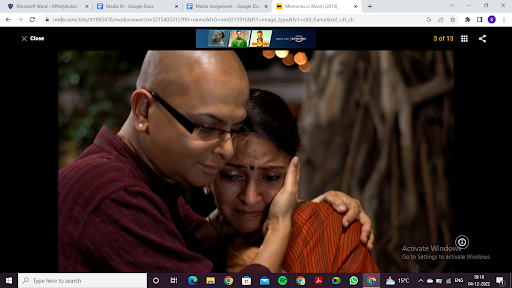

In Memories in March, unrequited love and grief play out differently. Here, Ornob loses his lover in a car accident. This unites him with Siddhartha’s mother, Aarti. The entire movie revolves around conversations between the two of them and their dealing with the grief of losing their loved one. In one of the recordings which Aarti found, Siddhartha says that he wants her to meet somebody and in the next year, they will be “one big family, you, me and Ornob.” The movie shows an acceptance on the part of the mother of how love exists in various forms while on Ornob’s part, it shows how one lives every day with the grief and pain of losing a lover, a partner. In the end, Ornob writes on Siddhartha’s Facebook page, “If I have to go away, can I leave a little bit of me with you?”

Conclusion

“But the real truth about you and me, is of no value to the world, brother”

This dialogue which Chapal says to Abhiroop in Arekti Premer Golpo captures the marginalization and exclusion which people from the queer community have to experience every day, just because of their identity. While there has been an increase in the production of queer movies, especially in neoliberal India and the proliferation of media coverage, the queer community still remains invisible and marginal to the public eye. While queer presence and visibility have expanded to digital platforms and many community spaces like Gaysi Family and the Queer Muslim Project have started voicing stories of “Desi Queers”, everyday exclusion, brutality and violence remain the lived realities of the queer community. Perhaps, more voices from the community, like that of Rituparno Ghosh, in different forms and shapes, will bring a change in this hetero-patriarchal world, or that is what we can hope for.

Written By: Shatarupa Paul

Author